Insights Into Parental Involvement

Parental Involvement from a Research Perspective

The partnership construct is

based on the premise that collaborating partners have some common basis

for action and a sense of mutuality that supports their joint ventures.

Teachers and parents have a common need for joining together in partnership:

the need to foster positive growth in children and in themselves. It is

their challenge to create a sense of mutuality so that their efforts are

meaningful to all those involved.

Research provides insight

on parent attributes that support meaningful partnerships. These attributes

include warmth, sensitivity, nurturance, the ability to listen, consistency,

a positive self-image, a sense of efficacy, personal competence, and effective

interpersonal skills.

Marital happiness, family

harmony, success in prior collaborations, and openness to others' ideas

have also been related to parental competence in promoting partnerships

(Swick, 1991). Schaefer (1985) has noted that parents who are high in self-esteem

are more assertive in their family and school involvement. Not all parents

achieve the competence that supports these attributes. Teachers can provide

a setting that encourages the development of partnership behaviors in parents.

Modeling respect and communication skills, showing a genuine interest in

the children, responding constructively to parent concerns, promoting a

teamwork philosophy, and being sensitive to parent and family needs are

some ways to promote this process. Lawler (1991) suggests that teachers

encourage parents to be positive through the example they set in being

supportive, responsive, and dependable.

Teacher attributes that appear

to positively influence teachers' relationships with children and parents

include: warmth, openness, sensitivity, flexibility, reliability, and accessibility

(Comer and Haynes, 1991). From the parents' perspective, these teacher

characteristics are desirable: trust, warmth, closeness, positive self-image,

effective classroom management, child-centeredness, positive discipline,

nurturance, and effective teaching skills. Researchers have cited the following

teacher attributes as highly related to successful parent involvement:

positive attitudes, active planning to involve parents, continuous teacher

training, involvement in professional growth, and personal competence (Epstein,

1984; Galinsky, 1990).

The research on parent involvement indicates

that parents and teachers can create viable partnerships by engaging in

joint learning activities, supporting each other in their respective roles,

carrying out classroom and school improvement activities, conducting collaborative

curriculum projects in the classroom, participating together in various

decision-making activities, and being advocates for children (Swick, 1991).

Integral to these activities are the various parent and teacher roles and

behaviors that make for successful partnerships.

Parenting roles are performed

within the family and within family-school relationships. Roles critical

to family growth are nurturing, teaching, and modeling. Within the larger

family-school structure, parents must carry out learning, doing, supporting,

and decision-making roles. Naturally, parents use these various roles across

contexts, but they emphasize particular roles as family or family-school

situations dictate (Schaefer, 1985). For example, recent findings suggest

that when parents sense an

inviting school climate, they emphasize nurturing

and supporting behaviors in their interactions with teachers; their participation

in the school environment also increases (Comer and Haynes, 1991).

Teacher roles critical to

the partnership process include the family-centered roles of support, education,

and guidance. Teacher roles that focus on family involvement in school

and classroom activities include those of nurturing, supporting, guiding,

and decision-making. Together, parents and teachers can foster their

partnership through such behaviors as collaborating, planning, communicating

and evaluating (Epstein and Dauber, 1991; Swick, 1991). (Swick 1-2).

Parents and teachers share responsibility for

creating a working relationship that fosters children's learning. It is

important for teachers and parents to remember that they know the child

in different contexts, and that each may be unaware of what the child is

like in the other context. It is also useful to keep in mind generally

that different people often have distinct but differing perspectives on

the same issue.

For many parents, a fundamental

part of the parenting role is to be their child's strongest advocate with

the teacher and the school (Katz, 1995). Other parents, however, may be

reluctant to express their concerns because of cultural beliefs related

to the authoritative position of the teacher. Others may have difficulty

talking with teachers as a result of memories of their own school years,

or they may be unsure of how to express their concerns to teachers. A few

parents may fear that questions or criticism will put their child at a

disadvantage in school.

Many parents may be surprised

to learn that teachers, especially new teachers, are sometimes equally

anxious about encounters with parents. Most teachers have received very

little training in fostering parent-teacher relationships, but with the

growing understanding of the importance of parent involvement, they may

worry about doing everything they can to encourage parents to feel welcome

(Greenwood & Hickman, 1991). (Katz 1-3).

According to Jere Brophy (1987),

motivation to learn is a competence acquired "through general experience

but stimulated most directly through modeling, communication of expectations,

and direct instruction or socialization by significant others (especially

parents and teachers)."

Children's home environment

shapes the initial constellation of attitudes they develop toward learning.

When parents nurture their children's natural curiosity about the world

by welcoming their questions, encouraging exploration, and familiarizing

them with resources that can enlarge their world, they are giving their

children the message that learning is worthwhile and frequently fun and

satisfying.

When children are raised in

a home that nurtures a sense of self-worth, competence, autonomy, and self-efficacy,

they will be more apt to accept the risks inherent in learning. Conversely,

when children do not view themselves as basically competent and able, their

freedom to engage in academically challenging pursuits and capacity to

tolerate and cope with failure are greatly diminished.

Once children start school,

they begin forming beliefs about their school-related successes and failures.

The sources to which children attribute their successes (commonly effort,

ability, luck, or level of task difficulty) and failures (often lack of

ability or lack of effort) have important implications for how they approach

and cope with learning situations.

The beliefs teachers themselves

have about teaching and learning and the nature of the expectations they

hold for students also exert a powerful influence (Raffini). As Deborah

Stipek (1988) notes, "To a very large degree, students expect to learn

if their teachers expect them to learn." Schoolwide goals, policies,

and procedures also interact with classroom climate and practices to affirm

or alter students' increasingly complex learning-related attitudes and

beliefs. A growing number of urban school reform initiatives seeking to

transform failing schools engage significant numbers of parents.

The initiatives strive to

change a school's culture; the quality of relationships among educators,

parents, and children; and students' educational outcomes. The initiatives

work toward effecting systemic change in a school, and they situate their

reform efforts within the context of the surrounding community. Further,

since schools alone cannot solve the problems imported into them from society,

some projects reach beyond schools; they draw upon the power of community

institutions, such as churches and civic groups, to improve schools and

aspects of life in the community that impact -education. Successful systemic

initiatives usually result in an increase in the quantity and quality of

the various forms of parent involvement identified by Epstein (1995), such

as parent volunteers in the school, and parents helping their children

with homework. Many such initiatives have succeeded in improving

student academic achievement and transforming the culture of schools (Lumsden

1-3).

The initiators of collaborative

reform projects tend to view a school and its surrounding neighborhood

as a part of an interdependent social ecology that must be understood as

a whole in order to identify problems and develop solutions (Heckman, 1996a;

Murnane & Levy, 1996; Lewis, 1997). They address the ways that the

strengths and difficulties in a school and neighborhood can affect each

other and the children in both contexts (Giles 1-3).

Parental Involvement from a Parent’s Perspective

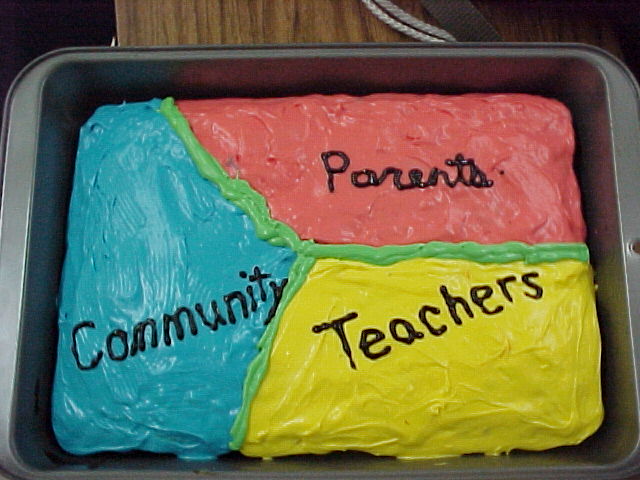

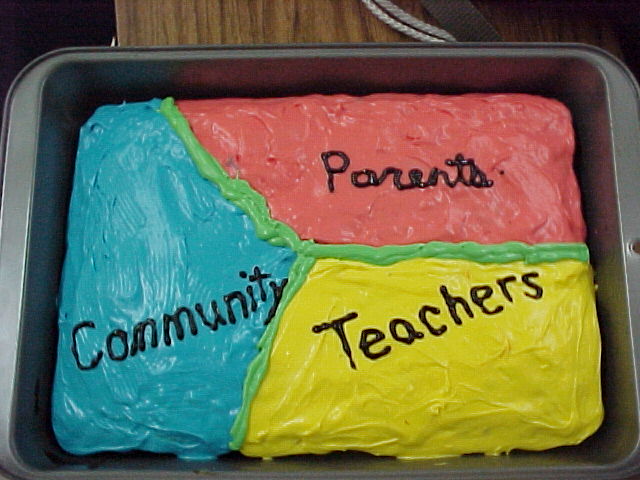

Many factors contribute to

a student's success or failure in school. Teachers, parents, and

the community can all influence students. Teachers are under a great

deal of pressure to teach students everything that they need to know.

Parents need to realize that education does not stop once the child steps

out of the classroom. Some parents just send their children to school

and expect them to get everything they need in those seven hours.

School environment, home environment, and community environment all interact

to create a student's overall learning environment.

Many parents know that what

they say and do has an effect on their child's performance in school.

However, there are complicating factors that obstruct parental involvement.

Time, cultural barriers, and lack of confidence in their own abilities

and input hinder parental involvement. Everyone involved in the education

of children need to be aware of these obstacles and think about ways to

overcome them.

Time is a large problem for

parents who want to take part in their child's education due to the increase

in the number of single parent families and the need for a two income household.

Life today is fast paced and full of activity for both adults and children.

Adults are often working during the day or night. Many employers

do not allow employees to take time off to take part in classroom activities.

Employers should be more understanding and encourage parents to interact

in the classroom and school activities. Parents also need to learn

to set aside special time to spend with their children. The

time a parent spends with their child will give the child security, support,

and understanding that their education is important.

The cultural make up of the

United States is changing rapidly. There are children from many different

backgrounds in schools all across the country even in the most remote and

rural areas. Language and beliefs may cause parents not to get involved

in education. Many of the immigrants speak very little or no English.

This causes difficulty or uncertainty about dealing with teachers and schools.

Socioeconomic differences also effect parental involvement. Low income

parents may not have the confidence to take part in the school setting.

These parents also may have little or no formal education which can also

cause problems. Perspectives and beliefs about schools and education

may vary greatly among these groups. Parents and teachers need to

be sensitive to these differences and take them into account at home and

in the classroom.

Parents who want to help their

children succeed may have reservations about what they can do. They

may not know how to help their child. Parents figure that the teacher

has the degree and he/she knows what is best for the child's education.

The parents may have limited education and feel very unsure of whether

or not their assistance would be useful or even wanted. With a little

bit of guidance and encouragement, these parents can learn that everyone's

input counts and is worthwhile. If parents feel that their

input is important and needed then they would be more willing to help their

children with homework or in other areas where the child may need help.

Parents who do not get involved may have had bad experiences when they

attended school. The school setting may bring back bad memories or

unpleasant feelings for them and they would rather just stay away.

There is no reason for parents to be intimidated when it comes to the education

of their children. Teachers are there to help the parents too.

Parents should not be afraid to ask questions and find ways to get involved

in their child's education.

Another aspect of parental

involvement completely takes place outside of the classroom but directly

effects a student=s performance. The home environment is important

to a child. Making sure that the student has his/her basic needs

met is vital to the child's education. Whether or not the child has

a safe environment, enough to eat, and a place to sleep and study make

a difference. Even if a parent cannot directly get involved in the

classroom activities, they can ensure that a child has the proper home

environment so that they can do their best at school. Also working

with the student at home is beneficial to the student. Reading with

them and helping with homework reinforces what is going on in the classroom.

Parental involvement goes beyond the classroom and any kind of positive

involvement is helpful to the student. Working parents can help by

providing materials for classroom use. Educational materials helps

to achieve a high quality education for the students.

Support for family involvement

in education should be widespread. Whether the family is a nuclear

family or made up of extended members such as step parents or grandparents,

everyone in the child=s life should take part in the education of that

child. In our community organizations such as the YMCA, Big Brothers

/Big Sisters, and afterschool programs along with the family interaction

helps to achieve a positive learning environment for every student.

When we make education top priority for everyone then our nation will truly

be successful.

Parental Involvement from a Teacher’s Perspective

Teachers are the foundation

of education and the major link between the school and the home. Teachers

have a wide range of responsibilities including keeping parents informed

about their child and actively seeking to involve parents in school activities.

Parental involvement can be a great asset or a tremendous burden upon teachers.

In this section, focusing on the teacher and parental involvement, we will

explore national goals and laws pertaining to parental involvement , several

ways teachers can communicate with parents, ways to have parents involved

in helping students with homework and involving parents in the classroom.

Parental involvement

is such an important issue, the national government has gotten involved

by including it in the Goals 2000: Educate America Act. (Parental Involvement)

“Every school will promote partnerships that will increase parental involvement

and participation in promoting the social, emotional, and academic

growth of

children.” (Goal 8- National Education Goals)

Under the Elementary and Secondary

Education Act (ESEA), Title I, Part A promotes partnership to benefit students

and parents as well as schools and communities. Part A of Title I acknowledges

the many roles parents play in their child’s education. Parental involvement

plans range from federal to state and local educational agencies (LEAs).

LEAs must submit a written parental involvement policy as part of Title

I, which “sets the expectations and establishes the framework for parental

participation in the LEA”. (Parental involvement)

With all of the

emphasis put on parental involvement it is extremely important for teachers

to communicate with parents at the beginning of the year. One of the best

ways to do this is to send home a parent information form. A parent information

form gives a teacher the opportunity to do two things, tell about what

the students will be doing and ask for information which will allow the

teacher to know the parent and student better while opening the lines of

communication. When telling parents what they can expect their child to

be doing teachers can briefly and broadly lay out the curriculum as well

as goals for students and different projects they will be participating

in. If you as a teacher need supplies for certain projects this is a great

opportunity to attach a list of things that will be needed throughout the

year. When you ask parents for information about their child it is always

important to include that the information is voluntary and only to help

you get to know the parent and child. The form lets parents know you value

their input, observations and expectations. The form’s content can be very

simple, just asking the parent to write about their child’s interests,

academic strengths and weaknesses and any information they feel you should

know. (Fisher 263)

On the first day of

school a parent information form is just one of several things you may

decide to send home to parents. Teachers should always include a way for

parents to contact them as well as a form for any medication that a student

may need to take and any special circumstances for their child. For example,

if the student is not going to ride the bus, a parent must send a note.

Sending information

home on the first day of school is the beginning of written communication,

which will be the most used form of communication between a teacher and

most parents. There are many types of written communication, including

newsletters on a weekly or monthly basis, letters, home/school journals

and progress reports. Newsletters can be sent home to inform parents about

what is going on in the classroom. The more parents know, the greater the

likelihood they will want to be involved. Newsletters also gives you, the

teacher, a chance to explain why you are doing certain projects and philosophy

behind them. Weekly newsletters can be more time consuming because of the

number of letters you are forced to generate, but they have advantages,

especially early in the school year. Early in the year the frequent letters

can acquaint parents with you and your teaching strategies. Monthly newsletters

can be sent later in the school year to keep parents informed. (Fisher

265)

A special letter can be sent

home at any time during the school year. A special letter may explain a

special project or ask for help from parents. Field trip permission forms

along with a letter asking for chaperones would be an example.

A home/school journal

can be a spiral notebook with the student’s name on it. As a teacher you

can simply write a few lines about the student and leave a place for parents

to respond. A simple letter in the front of the journal can explain how

it is to be used. This journal gives parents the opportunity to report

absences, request clarification, describe a home incident or volunteer

to help.

Progress reports can

be sent home periodically to explain students social and emotional growth

or academic progress in reading, writing and math. (Fisher 266)

The best way to communicate

with parents is through their child’s work. A portfolio of student work

can show improvement as well as strengths and weaknesses. Portfolios can

be time consuming, but are required by many schools. If portfolios seem

to time consuming, an informal portfolio, or just a collection of student

work can be beneficial. Students work can be very beneficial in parent

teacher conferences.

Helping students with

their homework is one of the most important things a parent can do. As

a teacher there are a few suggestions you can give to parents. First, suggest

that parents work with their child during a set time. It does not have

to be the same time every day, but a routine will help the parent become

accustomed to working with their child. Second, find a comfortable space.

It does not have to be desk, but should be somewhere comfortable where

neither the parent or the child will be distracted. Another method is to

use a timer. This method helps keep the student focused. (Troen)

Reading is another important

task that parents can help students with at home. Some good reading

tips include limiting television, keeping a list of books the child has

read and having the child read aloud. Parents being involved with student’s

work outside of class may not be something a teacher can physically, but

the results can definitely be seen in the classroom. (Troen)

A wonderful way for

parents to get a complete grasp on what is happening in the classroom is

to have the parent come in and help. This is an excellent chance for you,

as the teacher, to demonstrate how teaching and learning goes on in the

classroom. Parents helping in the classroom can almost always be a success

if you structure the experience correctly. Never put a parent in an uncomfortable

situation. Talk with the parent and find out what he or she is comfortable

with. It may be helpful to just let the parent observe at first, then move

them into working one on one with a student. (Epstein)

Another way to

have parents in the classroom is through Visitor’s Day. This is where students

invite family members to come into the classroom and see their work. This

can include extended family members as well as immediate family. It is

important to mention that not all children are raised by their parents

so always include anyone who is important in the student’s life. Visitor’s

Day can last about an hour and can be away to not only get parents involved,

but get students excited about their work. (Fisher 273)

Many parents have exciting

jobs which they would tell the class about so let parents know they can

contribute to the class in that way also. Parents who would not otherwise

come into the classroom will come and share something they feel confident

about and it can be a great learning experience for your class.

Teachers have an important responsibility

to make their class open to parents and to actively seek parental involvement.

Teachers must make every effort to keep lines of communication open and

work together with parents in a partnership for everyone involved.

Bibliography

“Creating the climate to support Parent and Family

Involvement”, (http://www.masterteacher.com/seminars/wk_pi.htm)

November

6, 1997.

Epstein, Joyce. “The Five Types of Parental Involvement”,

Center on Families, Communities, Schools, and Children’s

Learning.

(http://npin.org/ respar/ texts/passchoo/fivetype.html), 1994.

Fisher, Bobbi. Thinking and Learning Together, Heineman., Portsmouth, NH. 1995: 261- 262.

Giles, Hollyce C. Parent Engagement as a

School Reform Strategy. ERIC Digest Number 135. 1998.

(http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed419031.html)

Katz, Lillian G. and Others. Preventing

and Resolving Parent-Teacher Differences. ERIC Digest. 1996.

(http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed401048.html)

Lumsden, Linda S. Student Motivation to

Learn. ERIC Digest Number 92. 1994.

(http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed370200.html)

National Parent/Teacher’s Association. (http://www.pfie.ed.gov/faq2.php3)

National Parent/Teacher’s Association. (http://www.pta.org/programs/append.htm)

“Parental Involvement”, Policy Guidance for Tile

I, Part A. (http://www.ed.gov/legislation. ESEA/Title_I/parinv.html) April

1996.

“Parental Involvement in Children’s Education: Efforts by Public Elementary Schools”,

National Center for Education Statistics. (http://nces.ed.gov/pubs98/98032.html) January 1998.

Strong Families, Stong Schools.” (http://www.eric-web.to.columbia.edu/families/strong/key_research.html)

Swick, Kevin J. Teacher-Parent Partnerships.

ERIC Digest. 1992.

(http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed351149.html)

Troen, Vivian and Boles, Katherine, “Homework

Helpers, What parents need to Know from You.” Creative Classroom.

Nov/Dec.

1994: p.59.